I introduced a Northwest Coast Master Artist, Susan Point’s book on her limited edition prints. Her book: Susan Point: Works on Paper is readily available through online vendors and is a great addition to anyone’s Native American Art collection. My introduction reflects wet site art found through work along the Northwest Coast of North America and is reprinted here:

Showing the Wealth on Paper, Echoing the Archaeological Past

By Dale R. Croes

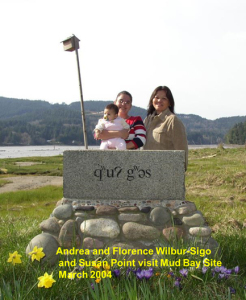

Jeff Cannell, Susan Point’s husband, contacted me a number of years back and asked me if I could show the couple a waterlogged archeological site we were excavating with the Squaxin Island Tribe. The site, in Puget Sound, Washington, is known as Qwu?gwes, a Lushootseed Salish name meaning a place to come together, a reference to the fact that archaeological scientists and indigenous cultural experts were working in partnership on it. It had been excavated in this collaborative fashion for eleven summers. I was a big fan of Susan’s work and was thrilled to be asked; I was also amazed when she told me later that it was the first archaeological site she had ever visited.

As an archaeologist I was just as surprised to be asked to help introduce Susan Point: Works on Paper. All my 40-plus-year career I have specialized in waterlogged or wet sites, which preserve wood and fiber artifacts excellently—typically up to 90 percent of the artifacts and material culture of ancient Northwest Coast peoples come from such sites. As in the title of one of her prints, Echoing the Past, Susan possibly felt that my exposure to the wealth of this ancient cultural art tradition might help describe some of her efforts to transmit it into our future.

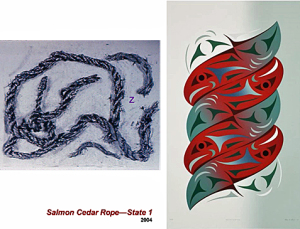

Many of Susan’s prints show this rich wood and fiber material culture. Sacred Weave, rich in symbolism, reflects the beauty of woven basketry thousands of years old, recovered from Northwest Coast wet archaeological sites. Musqueam Northeast, a three-thousand-year-old wet site in Susan’s own cultural territory on the Fraser River, revealed more than 125 examples of carefully woven basketry items—including pack baskets, 33 constructed with the checker weave shown in Susan’s print (Croes 1975, Archer and Bernick 1990). Also recovered were cedar bark string gill nets and three-strand twisted cedar bough ropes. The ropes were probably used as harpoon lines for hunting seals attracted to salmon caught in the ancient gill net. The cordage was twisted in a Z direction, just like Susan’s Salmon Cedar Rope—State I print here (which I proudly own). These are just a few examples of Susan Echoing [her Musqueam cultural] Past into the present and future.

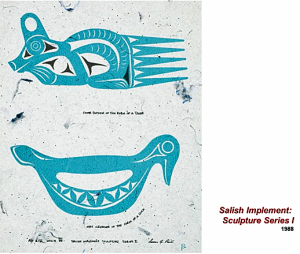

The Salish Implement, Sculpture Series I nicely shows two important items we see for millennium in the archaeological past—an ornate comb and mat creaser, the latter used in making sewn tule/cattail mats. As we know from the ancient Ozette wet site, a village on the Olympic Peninsula where entire houses were encased and preserved under a massive clay mudslide three hundred years ago, many utilitarian wooden items were beautifully sculpted as a matter of course.

Over fifty carved combs, mostly wooden, were found in the ancient Ozette houses (Kent 1975). These were typically worn as necklaces by Salish women, who would (and still do) use them both as hair combs and as scratchers. Touching one’s skin is/was considered improper (low class), so a comb serves/served that purpose. The Ozette examples, as in Susan’s print, often had elaborately carved figures on the handles and comb teeth either on one or both ends. One had separately carved teeth bound together in a fan; it may have been used for grooming wool dogs or for carding wool to create the roving used in yarn production.

The oldest know wooden comb, discovered in a three-thousand-year-old wet site on the Hoko River in Washington state, has 13 intricately carved wood teeth twined together at one end (Croes 1995:176–77). Also found at the Hoko wet site, at the western end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, was a beautifully sculpted wooden mat creaser, with two beak-to-beak belted kingfishers forming the handle. Susan’s print The Salish Implement, Sculpture Series I shows another water animal, a duck with the handle hole cut through its wing. The beak-to-beak kingfishers on the ancient creaser were of opposite genders, one with belt ruffles on its neck (female) and one without (male). Not only is the Hoko wet site mat creaser one of the oldest wooden sculptural art pieces ever found, being made and used at the time King Tut (Tutankhamen) ruled upper Egypt, but it was also painted, with the eyes and the head tuffs of the kingfishers painted in black (Croes 1995:174–76).

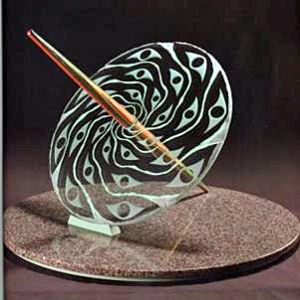

One of the most important Central Northwest Coast—Coast Salish and Makah—“machines†was undoubtedly the elaborately carved wooden spindle whorl, which generated most of the people’s wealth or “currencyâ€â€”the blankets. In the excavated Ozette plank houses, 23 were found, averaging an amazing nine spinners per household (Croes 2005:171–73, Draper 1989:6). Some were still on their wooden shaft, which had a slight knob on one end to hold in one’s palm and spin the loose roving of wool into tight spun yarn. The side facing the spinner or weaver was carved with an ornate design that she viewed as she made the yarn. Of the more than 160 of Susan Point prints in this volume, about 70—almost half—are based on this critical implement, the tool that produced the wealth, the yarn to weave the blankets—the Western equivalent of currency.

Since ancient and contemporary Central Northwest Coast peoples emphasize carved art in implements for making blankets, as Susan Point does here in spindle whorl forms in her print work (and elsewhere in her monumental sculptural work (Wyatt 2000)), this focus on blanket production equipment, past, present and future, needs to be explored. Archaeologists see spindle whorls, usually of bone or stone in dry sites and sometimes elaborately carved, in sites going back at least a thousand years, giving us some idea when the Central Northwest Coast spinning industry may have begun (Mitchell 1990:346–47, Carlson 1983:29–31). The sites with ancient spinners from this time period are concentrated in what is now called the Salish Sea, in archaeological sites of the southern Kwakwaka’wakw, Coast Salish in the Gulf, straits, and Puget Sound, and Makah/southern Nuu-chah-nulth on the west end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca (also suggesting a cultural time dimension for this inland sea, characterized as a single functioning estuarine ecosystem). Interestly, the Nuu-chah-nulth archaeological sites north of the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca do not have spindle whorls in their ancient or contemporary communities, meaning this blanket weaving complex was limited to Salish Sea traditions over at least the past millennium (Drucker 1950:194–95, McMillan 1999, personal communications 2013).

(Upper) 1,200 year old stone spindle whorl found at the Milliken archaeological site up the Fraser Canyon above Yale, B.C., Canada; (Center) Susan Point’s glass spindle whorl Looking Forward (2000) inspired by the 1,200 year old stone spinner found up the Fraser River; (Lower) Susan Point’s print Ancestral Vision (1994) depicting an 1,200 year old stone spindle whorl from up the Fraser River.

To better understand Susan’s 70 spindle whorl-based print designs, we should see how they fit into the complex blanket-weaving industry developed along the Northwest Coast. Along with the ancient and contemporary Central Northwest Coast spinners, the region developed true double-bar looms (the northern Tlingit {Chilkat}and Haida use single-bar hanging looms woven like baskets), weaver swords/batons, yarn spools and a domesticated source for yarn to make the wealth—wool dogs. Through husbandry and intentional breeding practices developed in the past millennium, a wool or hair dog was domesticated as a controlled source for the production of blanket yarn. Archaeological examples of these dogs (distinct from village dogs) are well documented and they were often reported by early Western explorers in the Makah and Coast Salish territories (Barsh, Jones and Suttles 2002:1–11, Gleeson 1970, Crockford 1997). In the entire American continent only two Native peoples domesticated an animal for its hair for spinning wool to make their textiles: the ancient Peruvians (Inca) bred alpaca from llamas and the ancient Salish Sea peoples bred wool dogs from the common dog to establish control over the production of the yarn they needed for blanket weaving. The Northern Northwest Coast people collected mountain goat wool, but on the Central Northwest Coast, where mountain goats are not native to the Olympic Peninsula and possibly Vancouver Island, the Salish Sea people domesticated and used active husbandry to control this critical aspect of their yarn production.

Paul Kane oil painting (1855) of a Lower Elwha S’Klallam scene showing all the major Salish Sea blanket weaving components: (1) the woman using a spindle whorl, (2) the true double-bar loom, (3) the twill plaited blanket, and (4) the domesticated wool dog.

Wayne Suttles, an anthropologist who specialized in Central Northwest Coast traditions, notes in Coast Salish Art that objects made by men and used by men were “usually undecorated or decorated sparsely.†In contrast, “implements made by men but used by women, such as mat creasers, spindle whorls, swords for beating wool, the posts of weaving frames (‘looms’), etc. were often, though not always, decorated with carving and/or painting†(Suttles 1983:86). He then wondered, “why should they use what appears to be the most structured style on one article, the spindle whorl?†(emphasis mine; ibid:86) We could ask the same question here: why are half of Susan’s prints focused on the wool spinners? Suttles and I have the same suggestion—“the answers lie in the use to which these implements were put, producing that other, essential source of power and prestige—wealth” (emphasis mine; ibid:86). And visible wealth—blankets one could produce—has been a primary medium of exchange along the Northwest Coast, from archaeological evidence of whorls, for at least a thousand years.

The Ozette village wet site again demonstrates the emphasis on wealth production in ancient households. Besides the 23 elaborately carved wooden spindle whorls, six wooden yarn spools, some with sculpted human heads on end knobs, were found (Daugherty and Friedman 1983:192–93). Fourteen decorated and slotted wooden loom uprights and loom roller bars were also uncovered, meaning that an average of three true looms were found per household—again emphasizing the industry of blanket weaving on complex shuttle looms, and not hanging looms as seen to the north. Ten wooden weavers’ swords/batons, possibly used as shuttle sticks, were also recorded, some with wolf-like carvings on their handles (Ibid:192).

Since soft organic materials such as hair, wool, hide, flesh and sinew do not normally preserve in wet sites, only one example of a multi-layer folded ancient blanket was found at Ozette, probably because it was in a concentrated pile and in a crushed wooden box (Gustafson 1980:16–17). This blanket was woven in the true-loom plaited twill weave with mostly white (likely dog) wool with dark elements added to create a distinct plaid design (best illustrated in Gustafson 1980:16).

Having conducted decades of archaeological work on the Northwest Coast, notably with the well-preserved wood and fiber artifacts from ancient wet sites, I have proposed that the cultural economies and arts seem to have evolved first in the Central Northwest Coast and then influenced the cultural directions of the arts and economies in the Northern (and possibly Southern) Northwest Coast. The archaeological evidence shows that some of the subsistence equipment, including ancient wooden fishhooks types, and art forms developed earliest in the Central Northwest Coast sites, around two thousand years ago in what is known as the Marpole Phase (Croes 1997:609–11, Croes 2001:164–66). With time this technology appears to have diffused from the Central to the Northern Northwest Coast, where it blended into the development and use of these cultural techniques and styles in later periods, including into the contact period. In a sense this is proposing that some of the evolving technologies and art styles of the Northern Northwest Coast reflect a diffusion or “spin-off†of cultural ideas developed at least two millennia earlier amongst the Central Northwest Coast populations.

For the arts, this would seem counter to the general anthropological perspective that the “center for the development of Northwest Coast Indian art†was the Northern Northwest Coast (Holm 1965:20). Squaxin Island Tribe master artist Andrea Wilbur-Sigo, a close associate and student of Susan Point, showed me how easy it was to transform Northern art elements into Coast Salish art elements, which may in turn have been a transformation from ancient Central Coast styles: the ovoids become circles, the U-forms become crescents and the split-Us become trigons (Andrea Wilbur-Sigo, personal communications 2013). In a sense she sees how part of this earlier cultural style shift could have taken place—simply evolving in a different direction on the Central Coast using the core elements developed earlier. This transition does not show a lessening of complexity in design, but rather a shift in focus by connecting the art to song, dance, vision and religion in a new trajectory for the Central Coast arts. Suttles states it well in Coast Salish Art: it “may have been the result of shifts in importance, back and forth, between the power of the vision and the power of the ritual word or shifts in the concentrations of wealth and authority†(Suttles 1983:86)—a dynamic part of Central Northwest Coast cultures today.

Susan Point takes her Salish cultural training, including echoes from the ancient past, and transmits the crucial elements into the future through her visions. This is a Salish tradition that has always influenced cultures around it, especially those to the north, but now also a Western culture residing in the nation’s traditional Salish Sea territories. This transmission moves the culture forward into new generations of Salish youth and continues to educate outside cultures about the considerable wealth of the Coast Salish. A focus on the spindle whorl reflects the making of Salish wealth—blankets—in spinning yarn from indigenous domesticated wool dogs, weaving on true looms and using ornate weavers’ swords/batons. Explaining the actual meaning of the spindle whorl designs is best done by cultural experts, such as by Susan Point in her discussions of her work here. Her work enriches our world community, becomes part of the world’s wealth, and is now compiled on paper here: Susan Point: Works on Paper (2014).

Dale R. Croes, Ph.D.

President, Pacific Northwest Archaeological Services

Adjunct Faculty, Department of Anthropology, Washington State University

References

Archer, David J.W., and Kathryn Bernick, 1990. “Perishable Artifacts from the Musqueam Northeast Site.†Manuscript on file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria, B.C.

Barsh, Russel L., Joan Megan Jones, and Wayne Suttles, 2002. “History, Ethnography, and Archaeology of the Coast Salish Woolly-Dog.†In Snyder, L.M. and E.A. Moore, eds., Dogs and People in Social, Working, Economic or Symbolic Interaction.Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Council of Archaeozoology1–11. Oxbow Books, Durham, UK.

Carlson, Roy L., ed., 1983 Indian Art Traditions of the Northwest Coast. Archaeology Press, Burnaby, B.C.

Crockford, Susan J., 1997 Osteometry of Makah and Coast Salish Dogs. Archaeology Press, Burnaby, B.C.

Croes, Dale R., 1975. “Musqueam Northeast Basketry and Cordage.†Manuscript prepared for Charles Borden, Musqueam Northeast report, on file at the National Museum of Civilization, Ottawa.

Croes, Dale R., 1995. The Hoko River Archaeological Site Complex, The Wet/Dry Site (45CA213), 3,000-1,700 B.P. Washington State University Press, Pullman, WA.

Croes, Dale R., 1997. “The North-Central Cultural Dichotomy on the Northwest Coast of North America: Its Evolution as Suggested by Wet-site Basketry and Wooden Fish-hooks.†Antiquity 71:594-615. Cambridge, England.

Croes, Dale R., 2001. “North Coast Prehistory—Reflections from Northwest Coast Wet Site Research.†In Jerome S. Cybulski, ed., Perspectives on Northern Northwest Coast Prehistory, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Mercury Series Paper 160:145-171, Hull, Quebec.

Croes, Dale R., 2005. The Hoko River Archaeological Site Complex, The Rockshelter (45CA213), 1,000–100 B.P. Washington State University Press, Pullman, WA.

Daugherty, Richard and Janet Friedman, 1983. “An Introduction to Ozette Art.†In R.L. Carlson, ed., Indian Art Traditions of the Northwest Coast, pp. 183–95, Archaeology Press, Burnaby, B.C.

Draper, John A., 1989. “Ozette Lithic Analysis.†Department of Anthropology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA.

Drucker, Philip, 1950. “Culture Element Distributions, XXVI: Northwest Coast.†University of California Anthropological Records 9(3):157–294. Berkeley, CA.

Gleeson, Paul, 1970. “Dog Remains from the Ozette Village Archaeological Site.†M.A. thesis, Washington State University, Pullman, WA.

Gustafson, Paula, 1980. Salish Weaving. Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver, B.C., and University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA.

Holm, Bill, 1965. Northwest Coast Indian Art, An Analysis of Form. University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA.

Kent, Susan, 1975. “An Analysis of Northwest Coast Combs with Special Emphasis on those from Ozette.†M.A. thesis, Washington State University, Pullman, WA.

McMillan, Alan D., 1999. Since the Time of the Transformers: the Ancient Heritage of the Nuu-chah-nulth, Ditidaht, and Makah. UBC Press, Vancouver, BC, Pacific Rim Archaeology series.

Mitchell, Donald H., 1990. “Prehistory of the Coasts of Southern British Columbia and Northern Washington.†In Wayne Suttles, ed., Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 7: Northwest Coast, 340–58. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Suttles, Wayne, 1983. “Productivity and Its Constraints: A Coast Salish Case.†In R.L. Carlson, ed., Indian Art Traditions of the Northwest Coast, pp. 67–87, Archaeology Press, Burnaby, B.C.

Wyatt, Gary, Editor, 2000. Susan Point, Coast Salish Artist. Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver, BC, and University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA.

Leave a Reply